How the search for extraterrestrial life helps sustainability on Earth

While astrobiology is focused on understanding the origin of life on Earth and its potential to exist elsewhere, tools and results from the field are also fueling advancements in sustainability here on Earth.

Sabrina Elkassas is a recent PhD graduate from the MIT-Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) Joint Program in Geomicrobiology/Chemical Oceanography. Her research focuses on microbial life in extreme environments by investigating locations on Earth with similar conditions, such as deep-sea hydrothermal vents and serpentinite mud volcanoes. She and her fellow coauthors Alta Howells, Catherine Fontana, Tristan Caro and Srishti Kashyap recently wrote a perspective in Nature Communications about how research into extraterrestrial life fuels advancements in sustainability research critical to Earth. Here, she explains how she’s seen this in her own research, and the reasons as to why astrobiology should be a two-way science looking up into the universe and down here on Earth.

Astrobiology is often framed as a science of distant places. It asks questions that feel expansive and abstract: how life began on Earth, whether it exists elsewhere in the universe, and what forms it might take on other worlds. These questions naturally pull our attention outward, toward Mars, icy moons, and planets orbiting distant stars. But astrobiology has always relied on Earth. To understand where life might exist beyond our planet, we study the most unusual environments and adaptations organisms have here, from deep ocean vents to alkaline springs, hypersaline brines, and the rocky subsurface.

What is becoming increasingly clear is that this work does more than inform space exploration. The same environments, organisms, and tools that help us search for life elsewhere can also help us respond to some of the most pressing challenges we face on Earth. In our recent Nature Communications article, my coauthors and I argue that astrobiology should be understood as a two-way science, one that not only draws insight from Earth to guide exploration of other worlds, but also brings knowledge back to support sustainability here at home.

Our motivations for this perspective stem from connections my coauthors and I drew between our own research and ongoing efforts in sustainability and biotechnology. My research focuses on methane-consuming microorganisms in a crustal serpentinizing oceanic environment on Earth characterized by hyperalkaline fluids, known as the serpentinite mud volcanoes of the Mariana forearc. Fluids effusing from these mud volcanoes can reach pH values as high as 12.5, comparable to oven cleaner! My coauthors work on similar microbial metabolisms in serpentinizing spring systems on land, as well as co-evolution of ancient microbes and Earth’s habitability, including cyanobacteria and early oxygenation. All of our individual projects are astrobiology-related, but have many applications for aiding our own Earth, including clean energy alternatives, resource conservation, and biomining, all considered in our perspective.

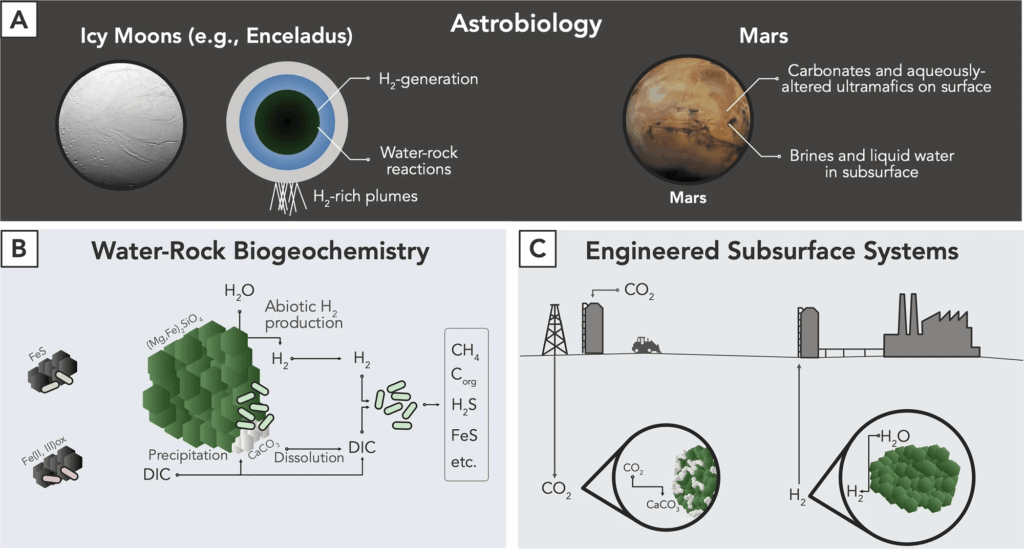

The first example we discuss in the perspective comes from the study of water-rock reactions in the subsurface. When certain types of rocks react with water, they produce hydrogen gas, a powerful source of chemical energy that can fuel microbial life without any input from the sun. These reactions, known as serpentinization, are of great interest to astrobiologists because they may be occurring today beneath the icy crusts of moons like Enceladus and Europa. They are also happening on Earth, where they support microbial ecosystems deep underground.

In recent years, the serpentinization process has begun to attract attention as potential sources of low-carbon hydrogen energy and as sites for carbon storage. Understanding how microbes respond to hydrogen and carbon dioxide in these settings turns out to be crucial. Microbial activity can either stabilize or destabilize stored carbon and can influence how much hydrogen remains available for capture. Decades of astrobiology and geomicrobiology research, much of it originally motivated by the search for life beyond Earth, now provides essential context for evaluating whether these technologies can work safely and effectively.

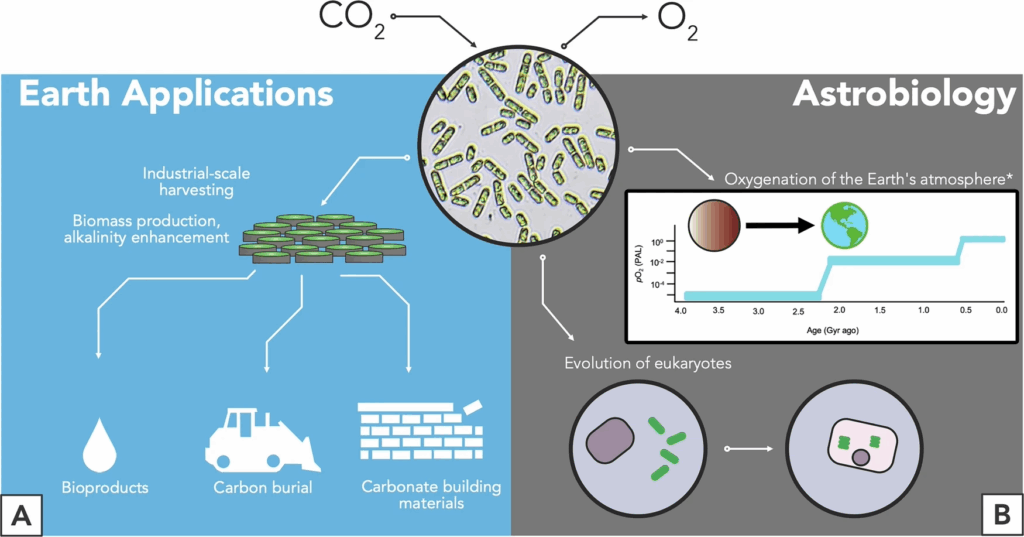

Astrobiology has also played a quiet but important role in biotechnology. Many organisms studied because they resemble hypothetical life on other planets have unusual metabolic capabilities that are useful on Earth. Cyanobacteria, for example, are ancient microbes that helped transform Earth’s atmosphere billions of years ago by producing oxygen. Today, they are responsible for fixing a large fraction of the carbon dioxide removed from the atmosphere each year. Because they are genetically tractable and metabolically versatile, cyanobacteria are increasingly being explored as platforms for carbon capture, biofuel production, and even the creation of living building materials.

Other organisms of interest include microbes that thrive at high pH, high temperature, or high salinity, conditions that are predicted to be common in planetary analog environments. These organisms produce enzymes and biomolecules that are usable in industries ranging from paper production to waste treatment and serve as sustainable and less environmentally damaging alternatives to the current technology.

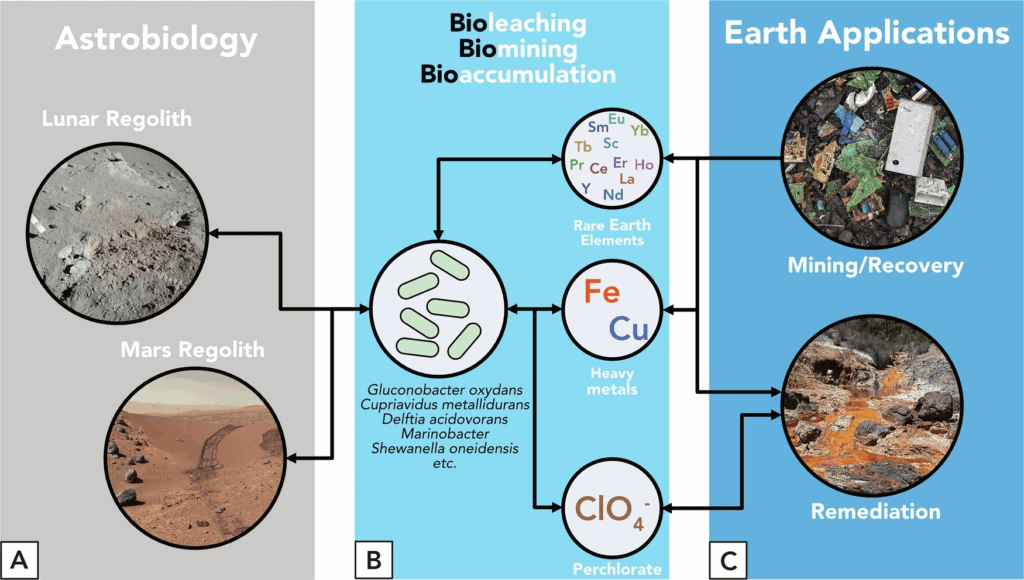

The connection between astrobiology and resource management becomes especially clear when looking at mining and remediation. Some of the best studied Mars analog sites on Earth are regions shaped by centuries of metal extraction, where acidic waters and iron-rich minerals support specialized microbial communities. These same microbes are now being used to recover metals with fewer chemicals and less environmental damage than traditional methods. Research originally designed to understand how life might persist on Mars has helped reveal biological strategies for recycling electronic waste, recovering rare elements, and cleaning up contaminated environments on Earth.

Many of these connections are already happening, but often in fragmented ways. Research funded to answer fundamental questions about life’s origins or limits may later find application in sustainability, without that possibility being acknowledged from the outset. We argue that being more deliberate about these links would benefit both science and society. Designing experiments, missions, and technologies with dual relevance in mind does not diminish the value of discovery. Instead, it expands its impact.

For early-career scientists like us, this dual perspective feels especially important. We are entering a field shaped by decades-long space missions at the same time as we confront accelerating environmental change on Earth. The tools we inherit from astrobiology, from studying extreme microbes to modeling energy flows through ecosystems, are well suited to both challenges. Embracing that overlap does not require astrobiology to abandon its cosmic questions. It simply asks the field to recognize that looking outward and caring inward can be part of the same scientific endeavor.

The search for life beyond Earth has always been motivated by curiosity about our place in the universe. As it turns out, that search may also help us better understand how to sustain the only planet we know for certain supports life: Earth.