Student Spotlight: Ciara Willis on balancing ocean research and fieldwork

Ciara Willis and Jessica Todd pose in front of their research ship, the RV Kronprins Haakon.

Marine biologist is a trendy job choice for young children, but when six-year-old Ciara Willis said it, she meant it.

“My classmates would be like, ‘oh, I want to be a marine biologist too!’ And I was like, ‘No you don’t, you just like dolphins,’ which was a bit judgmental, at six years old,” Willis says, “but ultimately, I was correct. They have completely different careers now.”

Willis held on to her dream, expanding it beyond just a wonder and fascination with the ocean, to a blunt realization of threats to its health like overfishing and warming waters. She’s now a biological oceanography PhD student in the MIT-Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Joint Program in Oceanography/Applied Ocean Science, and this past summer she’s been busy, with over four weeks spent on the sea and even more time spent conducting small boat-based field work.

“I just want to see this stuff. With COVID I spent a lot of time on my computer writing code. I want to go in the field and see all these weird fish,” she says.

When the COVID-19 pandemic halted fieldwork experiences, Willis was concerned that she wouldn’t have enough opportunities to get out in the field, which could reflect poorly on her CV down the line when she applied for post-doctorate positions and other forms of funding. Now that opportunities abound once more, she’s making the most of it.

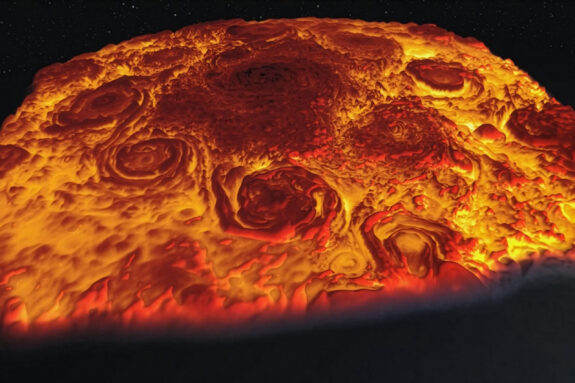

Her biggest research cruise this summer was on a Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI)-led project called the Ocean Twilight Zone, which is working to understand the ocean’s mesopelagic zone better. Willis was on one of three different ships that went out together to collect comprehensive data about food webs and carbon export in this area of the open ocean, located at a depth between 200 and 1,000 meters where light struggles to reach, earning it the name “twilight zone”.

Willis was on the biology and acoustic ship to collect data for her PhD thesis, which is looking at tuna and swordfish populations to get a sense of their eating and diving habits in these locations, and how changes in their food sources due to emerging twilight zone fisheries could impact their populations.

“We’ve seen so many problems over the past few decades, if not longer, with fisheries being overexploited and even fishery collapse,” she explains, “and that’s really damaging ecologically and economically.”

The other two ships collected additional information primarily through chemical research and capture of large predators via longline fishing. With three ships working at once, they were able to gather a uniquely comprehensive understanding of the food web in the area.

But not all of Willis’ research this summer will add chapters to her dissertation, and to her, that’s a good thing.

“I think you’re a better natural scientist if you’re exposed to different parts of the natural world,” she says. Participating in other projects not directly linked to her PhD research is not only a way to expand her general scientific knowledge, but also a way to develop technical skills for later down the line and meet new people in related fields.

For example, she spent some time on one project deploying acoustic instruments in the Virgin Islands to collect data on coral reefs and fine tune her scientific scuba diving skills with fellow Joint Program PhD Nadège Aoki, as well as shark tagging on another with the Shark Tagging Group from the University of Miami.

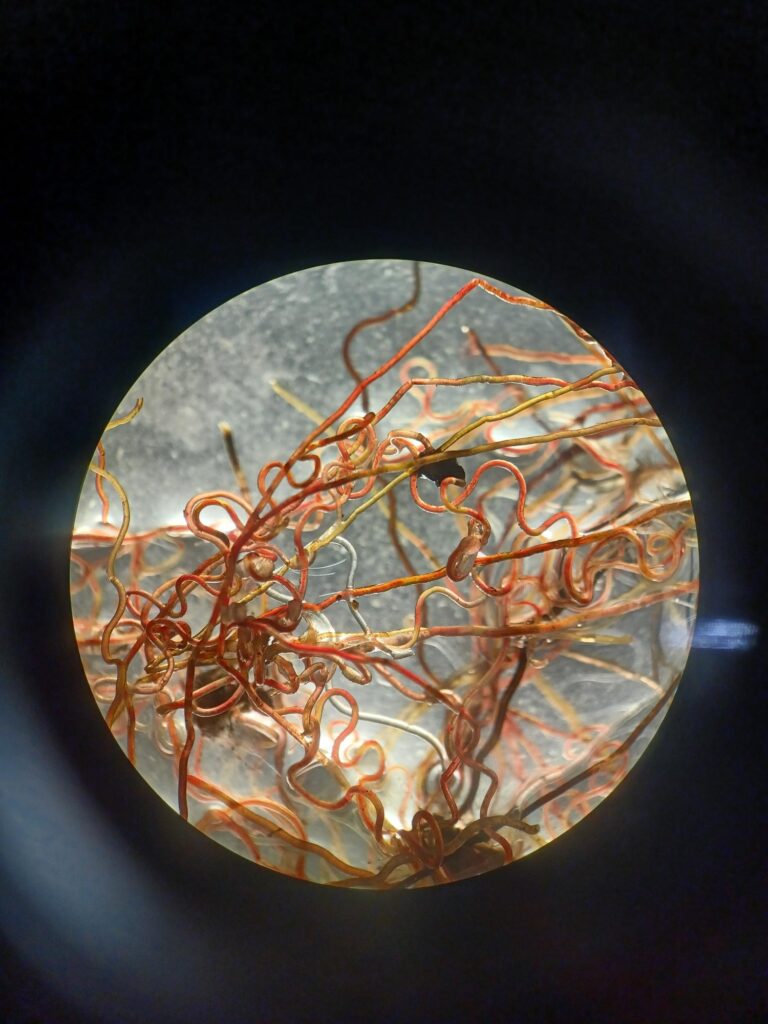

She also went on a cruise out of Svalbard, Norway sponsored by Advancing Knowledge of Methane in the Arctic (AKMA), a joint program between WHOI and the Arctic University of Norway that studies methane activity on the seafloor and in Arctic oceans. Willis helped conduct research related to meiofauna and macrofauna around methane seep sights, which are invertebrates that range in size from microscopic to the palm of your hand.

The trip also included educational outreach. The expedition brought together scientists, educators, philosophers, and artists to create educational materials about the ocean using all five senses, appropriately called the Ocean Senses project. Willis was on the vision team, in charge of creating an experience to replicate the low light environment of the deep ocean. As you go deeper in the ocean, low energy wavelengths of visible light (reds) are filtered out first, and high energy wavelengths (blues) penetrate the deepest. Because of this, animals that live deep in the ocean tend to be red as a form of camouflage. For her group’s project, they experimented with different filters on goggles so kids could see how the perception of colors change with different levels of light.

Willis believes that this kind of outreach is “super valuable” for PhD students to do. For one, it helps inspire the next level of scientists, but it also helps kids become more conscious of the ocean and sustainable practices, which is something everyone can care about. It also gets her excited about her own research all over again.

“I’m really happy that I was able to make up for a lot of lost time in terms of getting these field experiences that are very enjoyable, but perhaps more importantly, are really important for being a well-rounded scientist moving forward in my career,” she says.