MIT astronomy class asks the big-picture questions about the future of our species

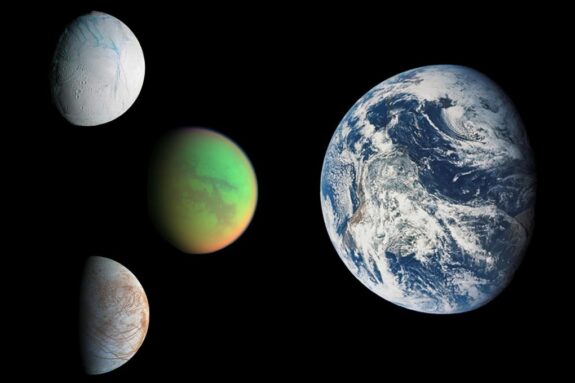

The class promotional image, showing the Earth as seen from the Moon, asks the question "How did we get here?", just one of many philosophical questions asked in 12.400, Our Space Odyssey.

What does it mean for humanity to become a multiplanetary species? What can we learn from that process about our relationship with Earth? How would evidence of life beyond Earth affect us as individuals and as a society?

These are just a few of the questions students may reflect upon in 12.400, Our Space Odyssey. The introductory astronomy course, which counts as a Restricted Electives in Science and Technology (REST) class, addresses big-picture questions about space exploration as humanity enters a new era of space exploration at a time where interstellar objects are found, the atmospheres of distant worlds are being explored, and humanity is returning to the Moon and traveling to Mars.

“The goal of the class is to provide a space where the student can reflect on these experiences, and how there could be opportunities to see change,” says Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Science (EAPS) Professor Julien de Wit, who teaches the class and revamped the curriculum a few years ago. “The last thing I would want is for us to be so unprepared that news such as finding life elsewhere would be lost between two tweets, and would just get our attention span for 30 seconds.”

It’s not a traditional class, where de Wit stands at the front of the room and lectures at the audience for the entire class period, promising answers to questions that are much more complex than just solving for x. De Wit, who runs the Disruptive Planets Group in EAPS, brings in frequent guest speakers, both from MIT and elsewhere, with expertise in fields from biology to neuroscience to theology to archeoastronomy, all to emphasize the collaborative nature of these questions.

Valentina Sumini, a visiting professor at Politecnico di Milano and a collaborator with the Space Exploration Initiative at MIT Media Lab, has been a guest speaker since the new curriculum launched. Sumini talks about space architecture and what a sustainable human presence in space might look like when building habitats on places such as the Moon and Mars. She says students have been active participants, especially in discussions about the ethical aspects of resources and sustainability on other planets and how it informs resource use here on Earth.

“I believe in the relevance of generating visions through a holistic approach to both didacticism and research,” she says. “Especially in the field of human space exploration because of its intrinsic multi-disciplinarity.”

But the future of humanity also relies on the future of Earth. In addition to exploring the universe, the class covers “Climate 101”, where they break down the basics of climate and climate change, and the challenges of living with finite space and resources.

Lee and Geraldine Matin Professor of Environmental Studies Susan Solomon came in as a guest lecturer to cover success stories in climate policy. She talked about the development of solar panels, and specifically the drop in cost by more than a factor of 10 in 10 years, and how this was made possible by the Kyoto protocol.

“It’s a great example of how policies can force the development of new technology and drive reduced cost,” she says. “That kind of thing doesn’t happen on its own, in my experience.”

The class isn’t just for astronomers or science majors, but anyone interested in tackling questions about the future of humanity. “We bring some context to scientists, and then we bring some science to the non-scientist. So we build a network of bridges to enable meaningful dialogue,” de Wit says.

“If you have the chance to take the class, I really recommend it,” agrees Rila Shishido, a senior in course 8 (physics) and 21M (music and theater arts) who took the class in 2021. “I think there is something everyone can take away from the class whether they be a space enthusiast, physics major, or someone with zero prior knowledge or experience with planetary science.”

Iana Ferguson, a junior in course 8 who took the class that same year, decided to enroll after watching the promotional video, calling it “captivating”, and was also pleased by the variety of topics covered.

“Even if you’re not interested in space itself, it still has something to offer,” she says. “It’s building your world view as well as your scientific knowledge.”

Some of the lessons still stick in her mind, such as the question “What is life?” that de Wit posed on the first day. She also enjoyed taking a break from the mathematical analysis she was learning in her other classes to learn to approach these big topics in different ways.

“The class really teaches you how to think about your world rather than teaching you about the world,” she says.

The class work involves weekly readings to prepare for class discussions, and rather than a midterm or final exam students write a final paper on a theme of their choice, related to a class topic. The intention is to compile a curated list of essays into a book in a couple of years so that others can read their thoughts about the future of humanity in terms of space exploration.

In addition to creating the book, de Wit hopes to make the class accessible to people beyond the MIT community through an online course offering and is currently working on doing so through additional online partners. He says that this will help diversify the voices being heard and really bring together different groups and opinions.

“By providing the space and the tools to reflect on these topics, we can increase the range of perspectives gained, enable a larger engagement on global topics, and thus improve the odds of navigating our shared future intentionally,” he says.

Pre-registration for the spring semester course of 12.400, Our Space Odyssey, opens December 1st. You can check out the syllabus on the class page. For further questions, email Professor de Wit at jdewit@mit.edu