The Creepy, Unbelievably Inspiring World of Deep Sea Parasites

Ocean hitchhikers and bodysnatchers abound in the ocean, from the surface down to the deepest trenches. The question is, why? And is it a good thing? We join benthic ecologist and MIT-Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Joint Program PhD student Lauren Dykman, along with DSV Alvin pilot Bruce Strickrott, to learn about the bizarre lives of marine parasites and how we study them.

Read this at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

To learn more about work that Lauren is doing you can go to the Mullineaux Benthic Ecology Research lab at go.whoi.edu/benthos

By Daniel Hentz

Transcript

BRUCE: This is back in Costa Rica on one of the first dives, we collected this big red crab. And I was told, “Get that crab!”

LAUREN: We pulled up some squat lobsters

BRUCE: And when we got it to the surface, I had gone into the main lab to see what it looked like. And as we peeled this sort of tail of the crab back, there was this big mass there.

LAUREN: It was this sort of big sack that hangs out over the crab’s brood pouch.

BRUCE: And I was like, “What is that?!”

DANNY: If you haven’t guessed it already, this is not a story about cute dolphins or pet octopuses.

LAUREN: Most of the squat lobsters we pulled up had this parasitic barnacle called a rhizocephalan.

BRUCE: It was this ochre mass.

LAUREN: But the rest of the parasite grows a rootlet system throughout the muscles of the crab, so it’s actually, like, growing roots through all of its tissue.

DANNY: This is the story of intestinal hitch-hikers, chest-bursters, and yes […] body-snatchers!

BRUCE: And then basically, either rides on it or directs it––I don’t know which––but it’s pretty creepy. It infiltrates the animal; and it doesn’t just do it for this species. It does it on the galatheid crab.

LAUREN: We jokingly, horrifyingly, call these parasites, “body-snatching, castrating-parasites.”

BRUCE: There are a lot of really creepy things at the bottom of the ocean. Nature finds all sorts of ways to be successful right?

DANNY: I’m Daniel Hentz from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Marine parasites like this barnacle abound in the deepest fathoms of the sea, especially around these volcanic cracks in the seafloor called hydrothermal vents . But the question is why? And is it actually a bad thing?

LAUREN: There definitely are parasites at vents. But are there enough of them or is it the right type of parasite interaction to have a huge impact on the host?

DANNY: Lauren Dykman, who you heard at the top of the episode, is a benthic ecologist and PhD student in the MIT-WHOI joint program. She’s also a proud parasitologist.

LAUREN: Oh yeah, right before calling you I was dissecting some things from the cruise. I do it––you know––on a weekly basis.

DANNY: Cards on the table, she’s hoping I fall in love with parasites too.

LAUREN: Whenever you can infect someone else with the interest, it’s great.

DANNY: Studying parasites on hydrothermal vent animals seems about as niche as it gets in marine science. And these ecosystems aren’t exactly easy to get to or hospitable, for that matter.

LAUREN: Right at the vent orifice you can have 400°C water. And an animal, for example, could be swimming in 2°C water, which is near-freezing, and then a meter or so later it could be near boiling.

DANNY: The vents are forced open by volcanic activity below the seafloor. And the reaction between seawater and magma adds another layer of extreme, making the environment oxygen-poor and very acidic.

LAUREN: These vents have high concentrations of heavy metals, which are toxic to life.

DANNY: What’s odd is that even in these extreme conditions, parasites seem to thrive more here than almost anywhere else in the ocean. During one study in 1980, scientists trawling the deepest waters along the New York Bight discovered that benthic, or bottom-dwelling fish had more parasites inside of them than those caught in the midwater. Of the more than 1,700 fish they collected, 80% had been infested with some kind of parasite.

It’s like the deeper we dip the proverbial net, the more parasites we find.

LAUREN: And they have to find that host in this entire big world of habitat that’s not viable.

DANNY: But how they make it viable is mindblowing. One parasite that Lauren’s particularly fond of has developed the most creative way to stay alive.

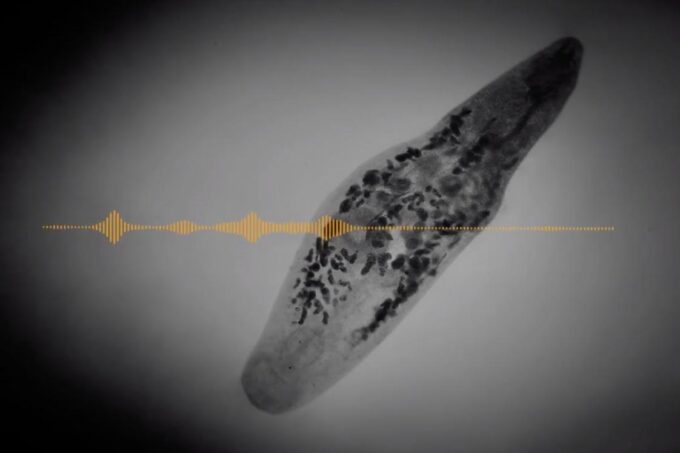

LAUREN: The great loves of my life in science have always been these parasitic worms, called diageneans.

DANNY: A type of tiny flatworm.

LAUREN: They use three different hosts in order to complete their life-cycle. So they have to pass through three different animals––three different species––to survive.

DANNY: Like a Trojan horse, it begins as a tiny, unassuming larva inside a vent snail or a gastropod. But eventually it asexually clones itself, until it tears the snail open.

LAUREN: And it just starts spewing larvae out of the snail. And these larvae swim free in the environment and they find their next host.

DANNY: …Jumping to another vent animal, usually something a little up the food chain, like a fish. And then…it does something bizarre. The worm asks to be put on the dinner menu.

LAUREN: They’re in this animal living as a cyst, and they’re just waiting for that animal to get eaten by a vertebrate.

DANNY: This whole process is called trophic transmission––just one of potentially limitless number of pathways toward survival. And so it was weird findings like this that beckoned Lauren to the deep sea to learn more about parasite biology.

LAUREN: If you’re going to be making any kind of statement or be any kind of expert in an ecosystem, it’s really important to experience that ecosystem first-hand.

DANNY: Over the years, pilots in WHOI’s submersible Alvin have taken scientists on countless trips to vent sites, thousands of feet deep along the East Pacific Rise. It’s a submarine mountain ridge that runs from Baja, California to Antarctica. Here, two massive tectonic plates are slowly spreading apart.

LAUREN: Where they spread apart there’s all of this geothermal activity, and that’s where the vents are located––they’re strung like pearls on a necklace, all the way down this mountain ridge.

DANNY: On Christmas Day, 2019, Lauren got her first chance to explore vent-life in Alvin. Together with the deep submergence pilot, Bruce Strickrott, she dove down to a site called V vent along the East Pacific Rise. At depth, they only have a few hours to make observations, in a landscape filled with crevasses, towering walls, and cathedral-like spires.

LAUREN: We were ready to work as soon as we hit the bottom.

DANNY: After 380 dives in Alvin, Bruce can tell you that catching parasites or their hosts requires superhuman focus and precision.

BRUCE: Imagine if you were trying to catch a moth and what you had was a butterfly net on a stick, and you were in a dump truck.

DANNY: On Alvin, “the butterfly net” is a vacuum-like arm called a “slurp gun.”

BRUCE: You can’t sneak up to anything on a submarine, as much as you might think you can. You’ve got blazing lights, so if they have any vision, they know you’re there. Plus, you can’t sneak through water with a 40,000 lb mass submarine. With the slurp guns in particular the way to get things is to not let them think you’re after them.

DANNY: Parasites themselves are typically too small to see anyways. To catch them, you really need to know who’s living inside of whom.

BRUCE: Some of these things are an inch long and the only time you get to see them is when they’re within a foot of the window. When it comes to things like parasites, I think you don’t even know you have a parasite until you get the animal that it’s associated with.

DANNY: That’s why Lauren had her face pressed to the sub’s viewport––looking for any sign of known parasites or their hosts.

LAUREN: I was looking at the crabs and squat lobsters, to see if there was evidence of these rhizocephalan.

DANNY: The funny thing is, while the crew doesn’t always return with the creature they set out to capture, they often bring back something new.

BRUCE: It’s not unusual for us to be diving in an area, and then we’ll go in the lab that evening and find out that they’re pretty confident that they’ve got two, three, even four new species, within just a dive or two.

DANNY: Right now the team is anticipating an underwater eruption along the East Pacific Rise, something that typically happens once every 10 years. But the question remains, with so much disturbance and so many extremes, why do parasites choose to set up shop here?

BRUCE: Life stands in the middle of the hottest place, knowing where it’s going to get roasted and defies the volcano for as long as it can, and then starts over every time.

DANNY: For Lauren, parasites serve as a sign of a healthy ecosystem. In the case of the vents, they show that this is a place with energy to spare.

LAUREN: Really diverse, functioning, healthy ecosystems actually have a higher diversity and abundance of parasites. So parasites can be a sort of symbol of an ecosystem being healthy and functioning properly.

DANNY: But, Bruce has a more philosophical answer.

BRUCE: I was having this discussion with my daughter this morning––I always take her to school. And she asked why ticks don’t get sick. But I was thinking about it. A tick or a mosquito is really nature’s way of delivering challenges to life, because life will stagnate without challenges.

DANNY: And maybe that’s it. Maybe these creatures, these fish and deep sea gastropods and tube worms, that learn to colonize the world’s most inhospitable environments, maybe this is the next challenge…parasites.

LAUREN: I know it sounds weird to say that I really respect and admire parasites. To see animals that are making a living in, first a very harsh environment, and then second in a way that requires so many pieces to fall into place, it’s very encouraging to see examples of resilience.

DANNY: To learn more about work that Lauren is doing you can go to the Mullineaux Benthic Ecology Research lab at go.whoi.edu/benthos

For the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, I’m Daniel Hentz.

Story Image: Image of a parasitic flatworm (Photo: courtesy of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)