Study reconstructs ancient storms to predict changes in a cyclone hotspot

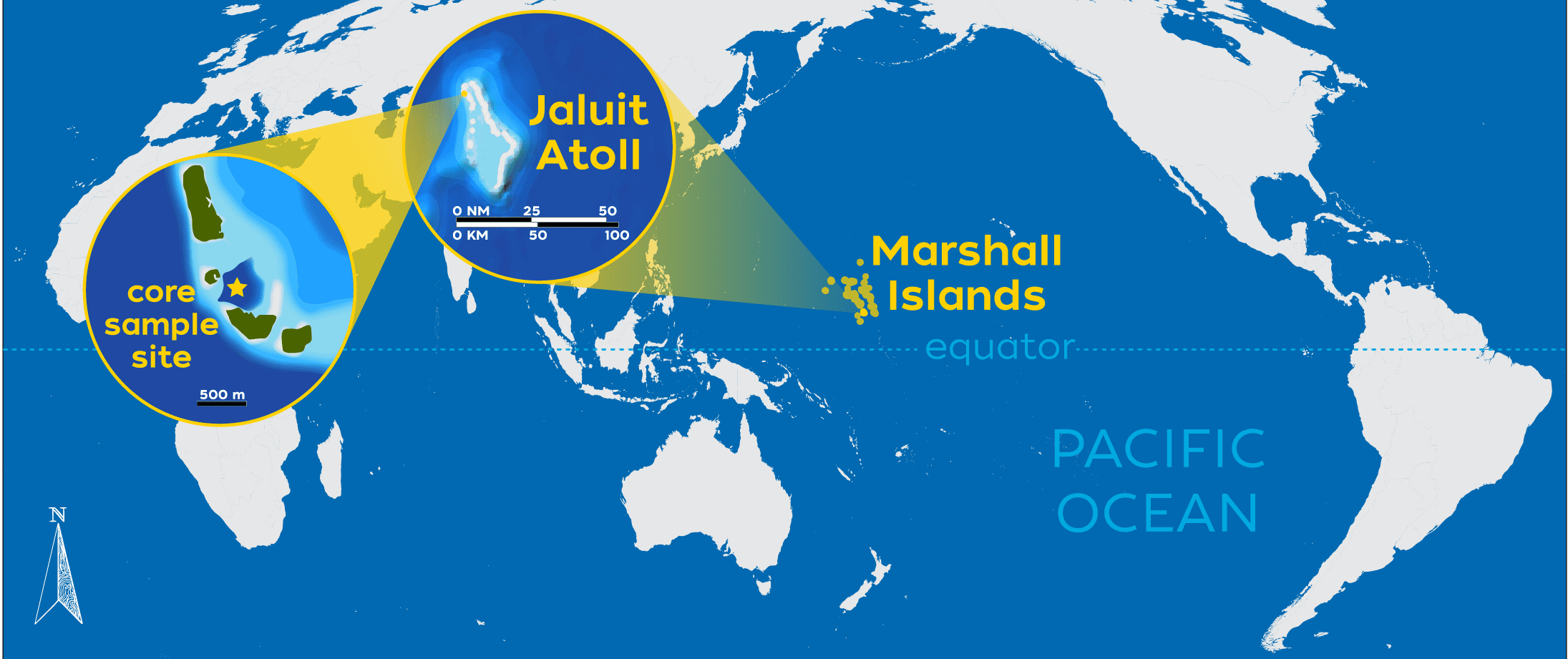

MIT-WHOI graduate student James Bramante reconstructed 3,000 years of storm history on Jaluit Atoll in the southern Marshall Islands.

Read this at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

Intense tropical cyclones are expected to become more frequent as climate change increases temperatures in the Pacific Ocean. But not every area will experience storms of the same magnitude. New research from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) published in Nature Geosciences reveals that tropical cyclones were actually more frequent in the southern Marshall Islands during the Little Ice Age, when temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere were cooler than they are today.

This means that changes in atmospheric circulation, driven by differential ocean warming, heavily influence the location and intensity of tropical cyclones.

In the first study of its kind so close to the equator, lead author James Bramante reconstructed 3,000 years of storm history on Jaluit Atoll in the southern Marshall Islands. This region is the birthplace of tropical cyclones in the western North Pacific—the world’s most active tropical cyclone zone. Using differences in sediment size as evidence of extreme weather events, Bramante found that tropical cyclones occurred in the region roughly once a century, but increased to a maximum of four per century from 1350 to 1700 CE, a period known as the Little Ice Age.

Bramante, a recent graduate of the MIT-WHOI Joint Program in Oceanography/Applied Ocean Science and Engineering, says this finding sheds light on how climate change affects where cyclones are able to form.

WHOI researchers reconstructed 3,000 years of storm history on Jaluit Atoll in the southern Marshall Islands. This region is the birthplace of tropical cyclones in the western North Pacific—the world’s most active tropical cyclone zone. (Map by Natalie Renier, ©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

“Atmospheric circulation changes due to modern, human-induced climate warming are opposite of the circulation changes due to the Little Ice Age,” notes Bramante. “So we can expect to see the opposite effect in the deep tropics—a decrease in tropical cyclones close to the equator. It could be good news for the southern Marshall Islands, but other areas would be threatened as the average location of cyclone generation shifts north,” he adds.

During major storm events, coarse sediment is stirred up and deposited by currents and waves into “blue holes”, ancient caves that collapsed and turned into sinkholes that filled with sea water over thousands of years. In a 2015 field study, Bramante and his colleagues took samples from a blue hole on Jaluit Atoll and found coarse sediment among the finer grains of sand. After sorting the grains by size and analyzing the data from Typhoon Ophelia, which devastated the atoll in 1958, the researchers had a template with which to identify other storm events that appear in the sediment record. They then used radiocarbon dating—a method of determining age by the ratio of carbon isotopes in a sample—to date the sediment in each layer.

Armed with previously-collected data about the ancient climate from tree rings, coral cores, and fossilized marine organisms, the researchers were able to piece together the conditions that existed at the time. By connecting this information with the record of storms preserved in sediment from Jaluit Atoll, the researchers demonstrated through computer modeling that the particular set of conditions responsible for equatorial trade winds heavily influenced the number, intensity and location where cyclones would form.

Jeff Donnelly, a WHOI senior scientist and a co-author of the study, used similar methods to reconstruct the history of hurricanes in the North Atlantic and Caribbean. He plans to expand the Marshall Islands study westward to the Philippines to study where tropical cyclones have historically formed and how climate conditions influence a storm’s track and intensity. Better understanding of how storms behaved under previous conditions will help scientists understand what causes changes in tropical cyclone activity and aid people living in coastal communities prepare for extreme weather in the future, he said.

“Through the geologic archive, we can get a baseline that tells us how at-risk we really are at any one location,” Donnelly says. “It turns out the past provides some useful analogies for the climate change that we’re currently undergoing. The earth has already run this experiment. Now we’re trying to go back and determine the drivers of tropical cyclones.”

Additional co-authors of this study include WHOI geologist Andrew Ashton; WHOI physical oceanographer Caroline Ummenhofer; Murray Ford (University of Auckland, New Zealand); Paul Kench (Simon Fraser University, British Columbia, Canada); Michael Toomey (US Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia); Richard Sullivan of Texas A&M University; and Kristopher Karnauskas (University of Colorado, Boulder).

This research was funded by the Strategic Environmental Research & Development Program, a partnership between the Department of Defense, the Department of Energy, and the Environmental Protection Agency.

Story Image: WHOI researchers reconstructed 3,000 years of storm history on Jaluit Atoll in the southern Marshall Islands. This region is the birthplace of tropical cyclones in the western North Pacific—the world’s most active tropical cyclone zone. (Credit: Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)