At MIT, Dara Norman ’88 fell in love with stars

Dara Norman on Maui at the site of the Daniel K Inouye Solar Telescope (DKIST) during its construction in 2016

At age nine, Dara Norman ’88 dreamed of becoming an astronaut. At 10, her skills in math and science convinced her that the dream was attainable. Then, while at MIT, she looked into a telescope for the first time, saw Jupiter, and fell in love with the stars. Astronomy was it for Norman.

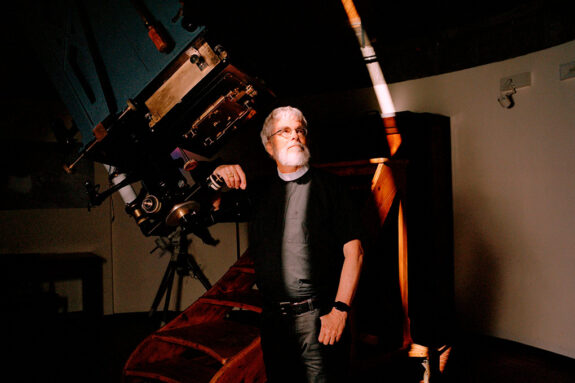

Growing up mostly in Chicago, Norman says that she had been to the local Adler Planetarium to see shows and exhibits, but somehow had never looked through an actual telescope, “not even a small one,” she says. “To look through the 16-inch telescope at Jupiter was literally life-changing for me. I just remember thinking that Jupiter actually looks like it does in the books—spot, bands, albeit in more of a gray scale.”

As a professional scientist, I have the opportunity to get paid to learn and investigate the physical world.

Her enthusiasm for studying the universe has only expanded over the years. Today, Norman is an astronomer and deputy director of the Community Science and Data Center at NOIRLab, a federally funded research and development center for ground-based, nighttime optical and infrared astronomy located in Arizona. “As a professional scientist, I have the opportunity to get paid to learn and investigate the physical world,” says Norman, whose research interests include studies of galaxy evolution, active galactic nuclei (the bright centers of galaxies where gas and dust are being accreted into supermassive black holes), and large-scale structures in the universe.

She credits MIT for giving her a variety of experiences during her time as an undergraduate. Although she earned a bachelor’s degree in earth, atmospheric, and planetary sciences (EAPS), she conducted research in several fields, including cognitive science and civil engineering. “MIT definitely shaped my perspectives,” she says. While the Institute provided Norman with many formative experiences, the astronomer also recognizes that it was challenging at times. She says she experienced anxiety and panic attacks, particularly during the beginning of her undergraduate career, noting that she was “taking too many classes in a single semester, including core physics, electrical engineering classes, and Japanese.”

It was during this time, though, that she took her first astronomy class with the late Professor Jim Elliot ’65, SM ’65, and things began to shift. She declared her major as EAPS and Elliot became her advisor, which made a huge difference, as she says he was “so helpful and so considerate, and so interested in helping me succeed.” She notes that this was also the start of understanding how important mentorship really is. “Mentors matter for your career pursuits, career satisfaction, but also for your mental health. Seek out mentors who can support you, but recognize that one person cannot support all areas in which you might need mentoring.”

After graduating from the Institute, Norman worked at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center for three years before enrolling at the University of Washington, where she earned a master’s and PhD in astronomy.

In addition to her work understanding how active galaxies form and why some are brighter than others, Norman is known as a leader in and advocate for inclusivity in scientific research, serving as the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy diversity advocate at the National Optical Astronomy Observatory. She seeks to expand the diversity of students and researchers from various backgrounds in the field, saying: “The truth is that STEM, like any other pursuit, is full of people, with their human flaws and biases. If we do not actively encourage and include a diverse group of people to join our ranks, there may be discoveries that never get made or take longer to achieve.”

In 2020, Norman was inducted into the inaugural cohort of American Astronomical Society (AAS) Fellows, and in 2023, she was selected as AAS president, a two-year term that started in June 2024. In this role, she hopes to continue to focus on inclusion and workforce development, particularly by promoting the expansion of access to data.

“It’s really where I have put a lot of my professional work these days, trying to make sure that folks that are at smaller places and astronomers of color have access to facilities, access to data,” says Norman. “We have a lot of data out there, and it’s become clear that people could achieve a lot of their scientific goals if the data is made available to them in a way that it is really useful. Advocating for making sure that that data is available to people, I think, is really important.”