Highlighting Women in Geobiology: Dr. Dawn Sumner PhD ’95

EAPS Summons Lab reconnects with alumni and revisits their work at MIT.

Story originally written for the EAPS Summons Lab

Current Role:

I am currently a professor at the University of California, Davis, in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences. I am also part of the Microbiology Graduate Group at UCD, as well as Chair of the Advisory Board for the Feminist Research Institute at UCD.

Research Foci and Initiatives:

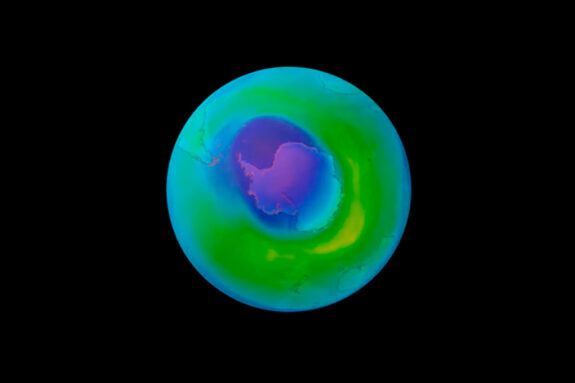

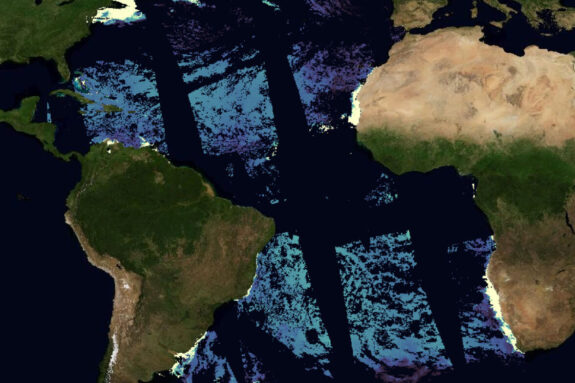

My main research interests are focused on how oxygenic photosynthesis evolved and how evolution, ecosystems and biogeochemistry interacted to transform Earth’s surface from anoxic to sufficiently oxic to support multicellular Eukaryotes. I am also part of the Mars Curiosity mission, working to understand habitability on Mars.

What drew you to geobiology and your current research?

I like exploring problems that are so difficult that they are essentially impossible to answer, and I also like making progress toward answering them. My current research projects have emerged from taking advantage of the most interesting opportunities at each point in time. I often make my choices based on wanting to work with people I enjoy spending time with and talking to. I also love fieldwork. The choices of people and places have led most of my career path.

For example, I chose to go to MIT for graduate school because I was inspired by the way John Grotzinger asked research questions. He suggested a project in South Africa where very little was known about some Archean carbonates — I was excited to jump into the unknown. Much later in my career, I was asked to help integrate the search for life on Mars into the Mars Exploration Program through some committee work. I became fascinated with the idea of how you look for something that might not exist in a scientifically rigorous way. That work eventually led to my participation in the Curiosity mission and as a Standing Review Board Member for NASA’s Perseverance rover.

About the same time, a colleague convinced me that there were stromatolites growing in Antarctic lakes that were a lot like the Archean ones I had been studying. And one of my graduate students brought microbiology into my lab. After several proposals, we got one funded to do extensive fieldwork characterizing the microbial communities growing in these extreme environments. That work led to many collaborations to understand how microbial ecology and biogeochemistry shape mat morphology as analogs for ancient stromatolites. Our work included genomics, which led to the discovery of new Cyanobacteria and closely related organisms that hold genetic clues to the evolution of oxygenic photosynthesis.

This research has become a major focus because I love the fieldwork and the science results are both insightful and unexpected. My lab group has a new project to explore how mats in Lake Fryxell, Antarctica, go from anoxic in the winter to containing “oases” of molecular oxygen in the summer due to photosynthesis. We expect to both get insights into how Archean environments changed with the first ecosystems based on oxygenic photosynthesis as well as how the organisms in modern mats change as they go from continuous illumination in the Antarctic summer to continuous darkness for four months in winter. This project is an international collaboration with some of the scientists I most like working with.

If you had unlimited funding and resources — what’s your dream research project?

Scientifically, my dream research project would be continued work in Antarctic lakes.

However, with unlimited funding, I would sponsor the research of early career women of color and genderqueer people of color in Earth sciences. I would establish a program for them to submit proposals, which would be evaluated and selected by their peers. I would make the funding rate 30%.

Why genderqueer/women of color? The systemic racism and sexism in science excludes the brilliance of most of these scientists. Others are excluded as well. I would choose genderqueer/women of color because their success will change the academic system in an effective and dramatic way based on both my observations of their influence and the high quality of their academic work.

Why require proposals? Writing proposals is a key part of science. In a proposal, one has to articulate questions and approaches that are linked in a meaningful way. I have found that writing proposals for funding is really important for focusing my efforts along productive avenues.

Why evaluated by their peers? Early career scientists are less set in their ways, on average, and more open to new, transformative ideas. Thus, the proposals selected will likely produce more diversity in results. Also, evaluating proposals to distribute limited resources helps the evaluators hone their critical scientific skills.

Finally, why a funding rate of 30%? In my experience, about 30% of the proposals I review deserve funding. That rate is high enough that it is worth the time spent preparing proposals and also requires the proposals to be scientifically sound. Those that aren’t funded can be resubmitted in response to reviews, usually leading to better science.

Do you have any advice for young women and girls interested in pursuing STEM?

Persistence is the most important aspect of a career in STEM. There are all sorts of barriers, ranging from failed research (which everyone faces) to racism and sexism (which differentially affect some people and not others). Create the networks, projects and support that can help you persist. I know that this isn’t always possible – and it’s why not all good scientists persist in STEM.

What’s the one thing you think folks should know about what you do?

I love what I do, very very much.

Story Image: Dr. Dawn Sumner in the field. (Credit: courtesy of Dr. Dawn Sumner)