Instagram users see Women Doing Science

The Instagram account Women Doing Science posted submissions from women in STEM fields to provide role models for young aspiring scientists, amassing 800 posts and 100,000 followers over four years.

What does a woman doing science look like?

The Instagram account Women Doing Science was founded in 2018 by then-PhD student Alexandra Phillips with the intention of showcasing women at all stages in their academic careers to help improve public perceptions of what it means to be a woman scientist.

Nearly four years later, the account has amassed nearly 100,000 followers who can view over 800 photographic profiles of self-identified women in science. When the number of viewers of Women Doing Science posts skyrocketed, Phillips and the rest of her team worked to analyze the metrics recorded with each post to discern how the account impacted aspiring women scientists.

The resulting paper, published last July in the journal Social Media + Society, details the potential for social media efforts such as Women Doing Science to act as a conduit to connect aspiring female scientists with diverse role models. Phillips and her co-authors found that audiences tended to reward posts that featured racially diverse and international scientists with higher levels of engagement in the form of likes, comments, bookmarks, and shares.

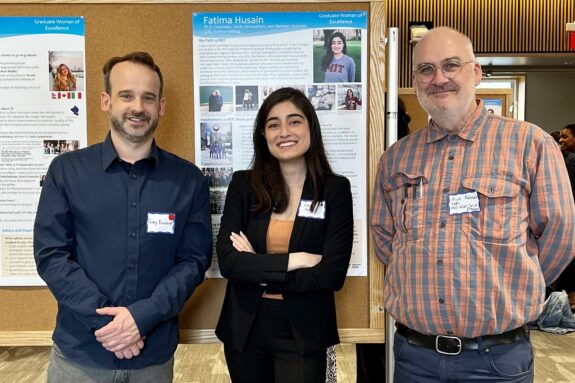

“Women Doing Science has had a really positive, demonstrable impact on future women scientists around the world,” says Fatima Husain, a PhD candidate in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences (EAPS) and co-author on the study. “This work shows that these initiatives really do matter.”

Diversity in Action

The Instagram account intentionally overrepresented certain demographics in response to long-standing low levels of diversity among women in the geosciences. One such category included Women of Color (WOC) and Black and Indigenous Women of Color (BIWOC) in the geosciences; while only 1.5% of geoscience PhD earners in the U.S. are BIWOC, their posts accounted for 13% of the account’s geoscience content. Another category they targeted was international diversity by featuring scientists outside of the U.S., who often included dual-language captions for their posts.

Overall, the authors found that posts featuring diverse scientists had higher engagement (the ratio of likes and interactions to the number of people who saw the post). Posts featuring WOC and BIWOC had higher engagement than non-WOC posts, while bilingual posts, especially ones from WOC, outperformed their English-only counterparts.

Data like this validates the personal accounts that women in STEM fields have always said.

“When I was growing up, I’d never even heard of a Pakistani woman in science,” says Husain, who is a first-generation American and a descendant of Pakistani immigrants. “I was so proud when [MIT School of Science] Dean Nergis was named because I’ve never seen a Pakistani woman scientist in such a powerful role. It’s inspiring and meaningful.”

Many EAPS alumna have been featured on WDS’s Instagram, including Gabi Serrato Marks PhD ’20, Kelsey Moore PhD ’20, Fatima Husain SM ’18, and Juliana Drozd SB ’22. Lily Dove, SB ’18, shared some images from her time aboard the RV/IB Nathaniel B. Palmer back in 2018.

“It was wonderful to get an outpouring of excitement from all over the world about my work,” Dove says. “Doing research can be isolating and even lonely at times, so it was wonderful to get a dose of energy from the followers of WDS.”

Challenging Perceptions

While public response to the account was primarily positive, some of the posts stirred controversy. One such post involved an image of a scientist in a biology lab with her hair down and wearing high heels; the post was inundated with comments criticizing the scientist’s stylistic choices, claiming they were unsafe in the lab or contributed to unrealistic standards for girls. While some commentors pushed back on the critiques, the post was temporarily archived.

“Some folks may have gotten upset because they too might have had rather rigid notions of what a woman in science ‘should’ look like,” Husain says. “Dispelling that sort of belief is the exact goal of this effort: to show you that there are endless ways to express yourself as a scientist.”

Now that the project is over the account is inactive, having posted the remaining submissions on a less frequent basis and highlighted the findings from the paper. But the takeaway from the account and the paper shows that simple measures like these that make women in STEM visible can make a big difference, both in science and other disciplines.

“I want folks to see this as like a starting point for a lot of impactful things that can be done on other social media platforms as well,” says Husain. “Now we have some data that shows that impact.”