Tracing persistent ozone-depleting emissions to their source

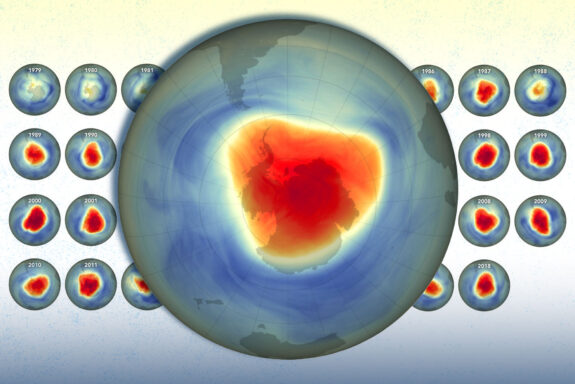

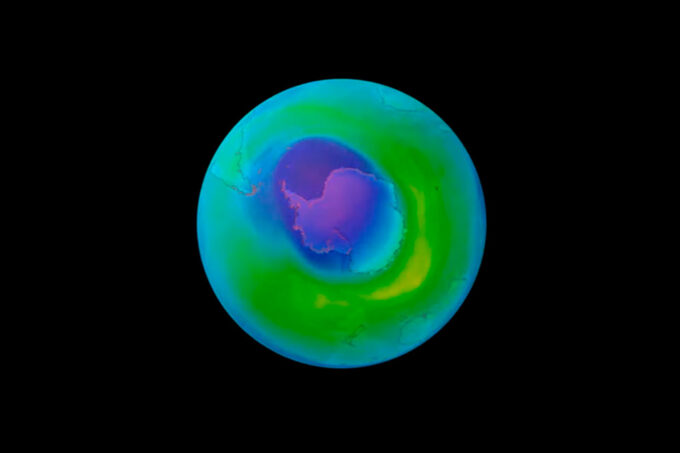

While the production and consumption of ozone-depleting substances (ODS) has been phased out since 2010 under the Montreal Protocol, emissions of one potent ODS—carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)—has continued to penetrate the stratosphere and slow down ozone layer recovery. Image credit: NASA

Ozone in the Earth’s stratosphere is a naturally occurring gas that serves as a planetary sunscreen, protecting living things from harmful ultraviolet radiation. While the production and consumption of ozone-depleting substances (ODS) has been phased out since 2010 under the Montreal Protocol, emissions of one potent ODS—carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)—has continued to penetrate the stratosphere and slow down ozone layer recovery.

In 2020, annual global CCl4 emissions accounted for roughly half of all global emissions of ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons. While scientists identified sources for most of those CCl4 emissions, about 30-40 percent remained unexplained.

Previous studies suggested China as a likely primary source of the remaining unexplained emissions, due to its leading role in the global chloromethane industry—currently considered the main source of CCl₄ emissions. To investigate their hypothesis, a team of researchers at the MIT Center for Sustainability Science and Strategy (CS3), University of Bristol, and other institutions, derived total CCl4 emissions from 2011 to 2021 in China using long-term atmospheric observations from a network of AGAGE and other sites across the country.

The researchers found that while China generated around half of global CCl4 emissions produced during this period—including about half of the 30-40 percent that had previously lacked an identifiable source—its CCl4 emissions did not increase alongside its expanding chloromethane industry. In fact, they showed a slight decline. Meanwhile, CCl4 emissions from allowed feedstock uses—such as in the production of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) and hydrofluoroolefins (HFOs), which are unregulated—became increasingly dominant.

These results appear in the journal Nature Geoscience.

“This study highlights the need to identify all major sources of CCl₄ emissions, including those still allowed under existing regulatory frameworks,” said Minde An, a postdoctoral associate at MIT CS3 and the study’s lead author. “In addition, potential legacy emissions from historical uses of CCl4, as well as byproduct releases from chlorine-related industries in other countries, warrant further attention.”

Quantifying the main contributors to the other half (beyond China) of global CCl₄ emissions “will require extension of our atmospheric measurements into potential emitting regions such as South Asia and South America,” said CS3’s Ronald Prinn, an MIT professor of atmospheric science and co-author of the study.