Exploring phytoplankton diversity

In a new paper, MIT-CBIOMES investigator Stephanie Dutkiewicz and collaborators use the Darwin ecosystem model to develop theories seeking to explain and predict phytoplankton biogeography.

Read this at MIT Darwin Project

Ocean microbial communities (phytoplankton) play an important role in the global cycling of elements including climatically significant carbon, sulfur, and nitrogen. Photosynthetic microbes in the surface ocean fix carbon and other elements into organic molecules, fueling food webs that sustain fisheries and most other life in the ocean. Sinking and subducted organic matter is remineralized and respired in the dark, sub-surface ocean maintaining a store of carbon about three times the size of the atmospheric inventory of CO2.

The phytoplankton communities sustaining this global-scale cycling are functionally and genetically extremely diverse, non-uniformly distributed and sparsely sampled; their biogeography reflecting selection according to the relative fitness of myriad combinations of traits that govern interactions with the environment and other organisms. Scientists at MIT are using sophisticated computer models to develop theories to explain and predict phytoplankton biogeography.

Stephanie Dutkiewicz is a Senior Research Scientist in MIT’s Center for Global Change Science (CGCS) and a member of Professor Mick Follows’ marine microbe and microbial community modeling group, the Darwin Project, in the Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences (EAPS) at MIT. Dutkiewicz’s particular research interests lie at the intersection of the marine ecosystem and the physical and biogeochemical environment. She is especially interested in how the interactions of these components of the earth system will change in a warming world. In recent work, Dutkiewicz’s focus has been on how ocean physics and chemistry control phytoplankton biogeography, and how in turn those organisms affect their environment. To do this she pairs complex numerical models with simple theoretical frameworks, guided by laboratory, field and satellite observations.

“Phytoplankton are an extremely diverse set of microorganisms spanning more than seven orders of magnitude in cell volume and exhibiting an enormous range of shapes, biogeochemical functions, elemental requirements, and survival strategies,” Dutkiewicz explains. “This range in traits plays a key role in regulating the biogeochemistry of the ocean, including the export of organic matter to the deep ocean, a process critical in oceanic carbon sequestration contributing to the modulation of atmospheric CO2 levels and climate. Biodiversity is also important for the stability of ecosystem structure and function, though the exact nature of this relationship is still debated. Studies suggest that diversity loss appears to coincide with a reduction in primary production rates and nutrient utilization efficiency, thereby altering the functioning of ecosystems and the services they provide. Diversity is important, but what factors control diversity remains an elusive problem. Diversity is also important for higher trophic levels, with different types/sizes supporting different foodwebs”

While biodiversity of phytoplankton is important for foodwebs, and marine biogeochemistry, the large-scale patterns of that diversity are not well understood and are often poorly characterized in terms of their relationships with factors such as latitude, temperature, and productivity. In a new study, Dutkiewicz and co-authors from MIT, the Institut de Ciencies del Mar, Spain, the National Oceanography Centre, Southampton, UK, and California State University San Marcos, use ecological theory and a numerical global trait-based ecosystem model to seek a mechanistic understanding of those patterns. The paper appeared in Biogeosciences this month.

Focusing on three dimensions of trait space (size, biogeochemical function, and thermal tolerance), Dutkiewicz et al’s study suggests that phytoplankton diversity is in fact controlled by disparate combinations of drivers: the supply rate of the limiting resource, the imbalance in different resource supplies relative to competing phytoplankton demands, size-selective grazing, and transport by the moving ocean.

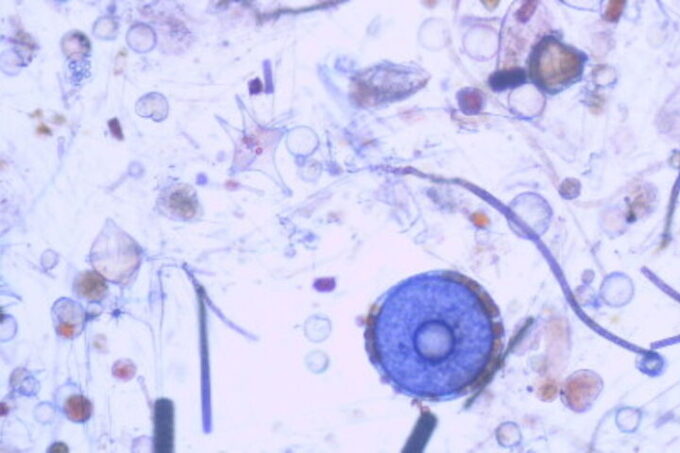

Model diversity measured as annual mean normalized richness in the surface layer. Normalization is by the maximum value for that plot (value noted in the bottom right of each panel). (a) Total richness determined by number of individual phytoplankton types that coexist at any location; (b) size class richness determined by number of coexisting size classes; (c) functional richness determined by number of coexisting biogeochemical functional groups; (d) thermal richness determined by number of coexisting temperature norms. (Credit: courtesy of the authors)

“Using sensitivity studies, we were able to show that each dimension of diversity is controlled by different drivers,” Dutkiewicz explains. “A model including only one (or two) of the trait dimensions will exhibit different patterns of diversity than one which incorporates another trait dimension.”

Dutkiewicz says, “I believe this is one of my more exciting papers, and really addresses some fundamental components of marine biodiversity, as well as highlighting why we need to be very careful in what we are defining as diversity. Our results indicate that trying to correlate diversity with quantities like temperature, or productivity (as is frequently done) is doomed to fail or worse to give wrong answers. There is no one mechanism that controls biodiversity. Understanding at the “dimensions” level is essential.”

Story image: Adapted from phytoplankton microscope image collected on a HOT cruise (Credit: courtesy C. Follett)