NASA selects project investigating ocean worlds and organic molecules in the search for life beyond Earth

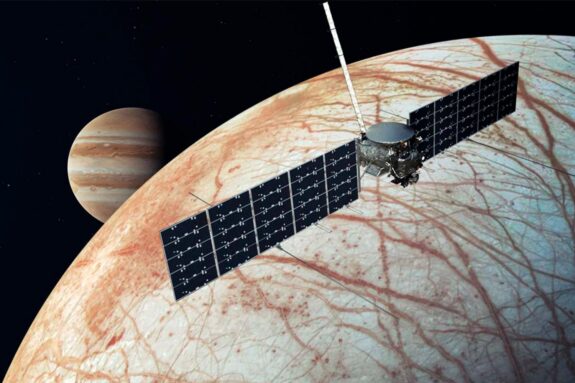

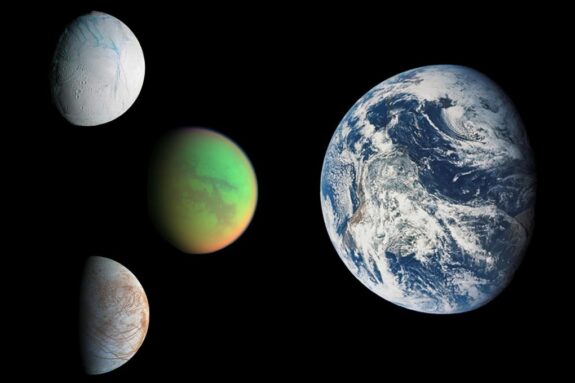

Ocean worlds such as Jupiter’s icy moon Europa and Saturn’s counterpart, Enceladus, could be among the most favorable places to discover life beyond Earth—and perhaps even a second, independent origin of life. With NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft scheduled to arrive at Europa in 2030 to determine whether its icy crust or under-ice ocean might be able to support life, the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) has recently been selected by NASA to lead a five-year project that will combine a wide range of scientific disciplines to investigate ocean worlds in new, collaborative ways. The project is slated to begin in 2026.

The Investigating Ocean Worlds (InvOW) project will seek to improve the analysis of data related to carbon-rich molecules that could be an indicator of biological activity and that will be a focus of future life-detection missions. According to Chris German, WHOI senior scientist and InvOW principal investigator, the new project will investigate how physical, chemical, and possibly biological processes active on ocean worlds like Europa or Enceladus might affect data collected by future space missions that hunt for signs of life.

“If you are alive today, this is the first generation where the question of whether there is life elsewhere in the universe could be answered in your lifetime,” said German. “Previously, this was an abstract, intellectual, and philosophical question. We now know enough to say that it is entirely plausible that there is life out there, within humanity’s reach, and we just need to go and look.”

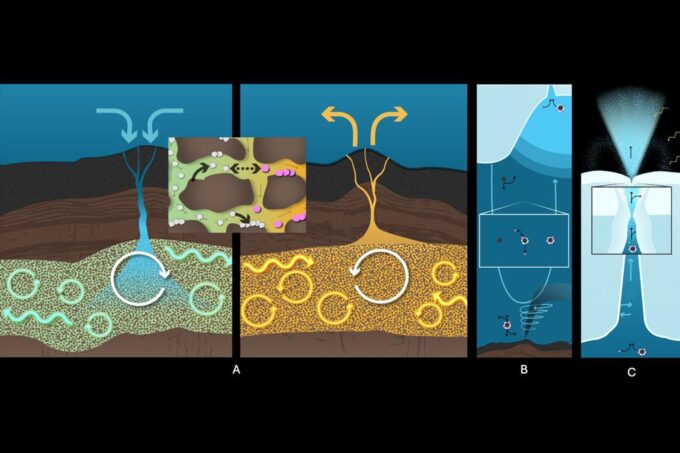

The InvOW project team spans 16 laboratories across the United States and will integrate a combination of disciplines (ocean, polar, and space sciences) and use interdisciplinary approaches (theoretical modelling, laboratory experiments, and fieldwork) to investigate three different domains on ocean worlds: the rocky subseafloor, the ocean itself, and the icy outer shell, known as the cryosphere. A unifying focus will be to investigate how organic materials—potentially indicative of life—might be modified as they travel through Europa’s or any ocean world’s different domains before they reach a spacecraft’s detection system.

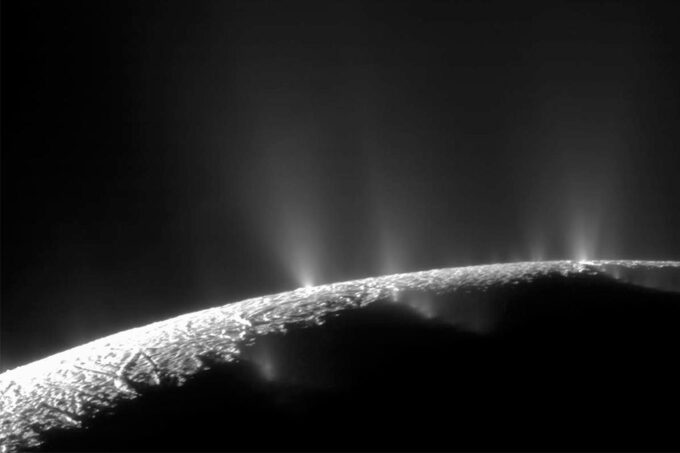

Homer A. Burnell Career Development Professor Wanying Kang, in MIT’s department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences (EAPS), is aiming to develop the first model capturing the interaction between the dynamics and chemistry of ocean floor geysers on Enceladus. By simulating the ejection of materials from these geysers, she is hoping to understand how biosignatures are transported in the ocean.

“The ejecta may be the key to answer the habitability of Enceladus’ ocean,” she said. “With this support, we can better understand what we expect to see if the ocean is inhabited.”

The Investigating Ocean Worlds project builds on the NASA-funded Exploring Ocean Worlds (ExOW) initiative that German also led and that involved a number of the same scientists, including Kang. While the earlier project focused on understanding physical and geological processes on ocean worlds, InvOW focuses on what German describes as the biggest problem to confront: making sense of any organic molecules detected from future ocean world missions, starting with the Europa Clipper.

“During this period while the Europa Clipper is heading to Europa, let’s prepare by focusing on this one specific thing: How do you measure organic compounds and know whether they are indicators of life or habitability, or perhaps of nothing specific,” he said.

For more information on the other aspects the mission will cover, read the entire WHOI press release